The South African

The South African

Introduction

The military potential of manned balloons was anticipated long before the Montgolfiers managed to achieve the first tentative lift-off of a man-carrying 'aerostat' in 1783. This was but the preface; it was in 1794 that Revolutionary France wrote Chapter 1 at the battle of Fleurus. They put an observer into a wicker basket suspended beneath a tethered hydrogen- filled balloon, his job being to observe Austrian troop dispositions. Other European countries took notice and soon small military balloon units were established, rather tentatively, in a few armies. Their relatively extensive use (for the times) in the American Civil War of 1861-5 gave a further push to the concept, and marks the point at which the British Army began to toy with thoughts of aerial reconnaissance. Little by little, spare time activities by enthusiastic Royal Engineers(REs) and others became formalised, and by the early 1880s a small but professional RE balloon unit came into being. The balloon envelopes were made of expensive but almost gas-tight goldbeater's skin (created laboriously from theskin of ox caeca) and were filled with hydrogen that could now be made at a base facility and transported in high-pressure cylinders. The balloons were spherical and bobbed and twisted about even the slightest wind, making detailed observation of the ground often difficult.

(Think of a helium-filled balloon on a length of string being towed along behind a running child, or the same child - and balloon - standing still on a windy day.

And the Germans were already developing a far more stable sausage-shaped design which the British did not adopt until about 1915.) British balloons first went on active service in Bechuanaland (now Botswana) in 1884, and the following year were taken on the Suakin expedition. Their next outing was to South Africa at the start of the 1899 war against the Boer Republics.

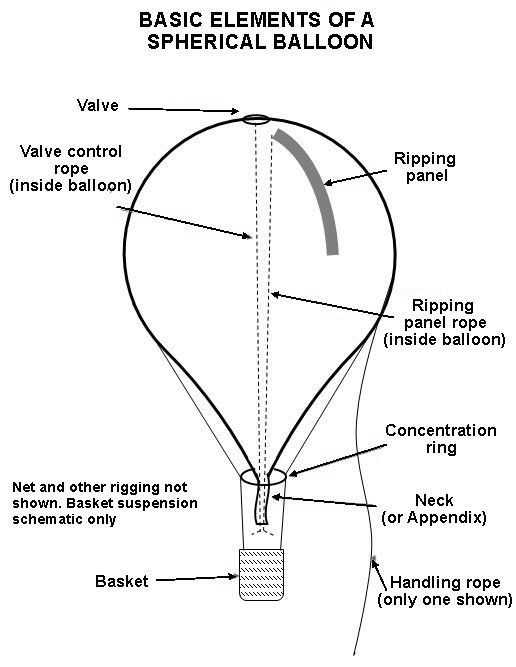

Fig. 1 Basic elements of a spherical balloon

Once Pretoria and Johannesburg were occupied in mid-1900, the war ceased to be one of 'formal' battles and mutated into a guerrilla war. Balloons played a useful role in the first phase, but were unsuited to the second, and left the theatre soon after it began.

So while the British balloon unit was already firmly established when the Anglo- Boer war began (11 October 1899), it was too small: only four officers, forty other ranks, and no horses. Hence a rapid expansion ensued, virtually anyone with previous experience in the unit being recalled. The existing unit was split into two, the resulting cadres being augmented as men and supplies came to hand to create Sections 1 & 2. A little later, as further equipment became available, a Section 3 was created.(2) In addition two active service Depot units were established (for Cape Town and Durban) each with its hydrogen generating and compression plant. To cope with this sudden growth, balloon production was gradually stepped up in England from a rate of about one per month to two, and ultimately a total of 30 balloons were sent out to South Arica.(3)

The story of the balloon units in South Africa is mostly a patchwork of scraps culled from all over, for no official account seems to have been compiled, or if compiled has been lost or destroyed along with many other early documents that fell foul of disaster or over-zealous clear-outs.(4) Moreover, the Official History mentions balloons but briefly (their involvement in the actions at Magersfontein(5) and Paardeberg(6))- suggestive that many in the Army's upper echelons considered them an insignificant element in the overall picture. The other major account, Amery's The Times History, has rather more balloon mentions, but all are of a somewhat passing nature.

Balloon Section 1

Happily, a day-by-day diary of the 1st Balloon Section's operations still exists(7), probably written by its officer-in-charge, Capt. H.B. Jones. The Section arrived in Cape Town aboard the Kildonan Castle on 22 November 1899 with 3 officers, 34 NCOs and other ranks, three wagons (three more arrived soon after), eleven balloons and equipment for the generation, storage, and compression of hydrogen. (While the electrolytic method of hydrogen generation was now in full use back at Aldershot, it was not suitable for use in the field and - as always planned - gas was generated in South Africa via the zinc/acid method.(8)) They were assigned to the main column (Cape Town-Bloemfontein-Pretoria) and while a base detail began work on setting up a depot in Cape Town the Section moved forward by rail. Thus began what was probably the most extensive and varied experience of all the Sections (for the 2nd Section was soon trapped in Ladysmith, and the 3rd didn't arrive until the 'formal' war was half over.) On 9 December they finally linked up with forces of Lord Methuen as he prepared his first attempt to push General Cronjé off the Spytfontein Ridge and its high point at Magersfontein kopje. This was the last significant blocking position before Kimberley, some 23 miles (38 kms) further north.

It was a pity the balloonists had not arrived two weeks earlier, for at the preceding battle of Modder River, Methuen's forces had received a drubbing from unseen Boer positions a balloon ascent might have revealed. It was an equal pity they had not arrived at the Magersfontein position a day or two earlier, since by the time they had inflated their first balloon, the 10,000 ft³ (285m³) Titania(9), on the morning of the 11th, it was too late for any observation to affect the catastrophic outcome of Methuen's attack. For the Boers had dug in at the foot of the kopje and not, as assumed, on its crest. Although they had successfully camouflaged their trenches from being seen from in front, an aerial view would probably at least have hinted at the truth. As it was, Titania made a series of morning ascents from Methuen's HQ position on a small kopje (now known as Headquarters Hill) but could add little to what was already known through the failure of the attack. Yet an afternoon ascent brought a moment of excitement: the Boers have left a huge gap - nearly 1500 yards (2km) - on the left of their line - an advance there will outflank their position! But almost as soon as the message was telephoned down, another followed: too late - they've woken up to the gap and their gallopers are closing it.(10) Soon the afternoon wind compelled the balloon to haul down, and the Section moved back.

A curious verdict on the Magersfontein balloon comes from Major Baden Baden- Powell(11) - curious, because he was himself a balloonist and a great advocate of man-lifting kites as observation platforms. It illustrates the shortfall in the average officer's understanding of aerial observation.

Indeed, in the presentation from which the above passage comes, Baden-Powell reveals further examples of misunderstanding that would no doubt have been widespread among the officers and men of the infantry.

The answer, of course, to the objection quoted above is that the balloon observer had powerful field glasses, and was looking down (albeit at a shallow angle) onto the Boer position, his view unobstructed (as was that of prone infantry) by scrub and the camouflaging vegetation placed in front of the trenches. Nonetheless, a modern author believes Baden-Powell's opinion, that the balloon was too far back, has considerable merit.(13)

The balloon ascended again on the 13th and reported that despite some insignificant movements the Boers were sitting tight - news Methuen did not want to hear. On the 15th December they moved forward in the early hours towards the ridge and attempted an ascent at daylight, but the wind rose as well, and Titania was beginning to leak badly. Some hurried patching was carried out, but they were ordered to retire; as they began to pull back a gust caught Titania and ripped her open, terminally.

Although they had not been able to offer anything of great significance to the fighting, in his subsequent despatch Lord Methuen generously expressed himself pleased with the little they had contributed:

At the time he gave the Section carte blanche to carry out future ascents on their own initiative as they saw fit - and they had many opportunities, for the Boers remained in position until mid-February.

On 17th December they filled Duke of Cambridge (8000ft³/225m³) from their remaining stock of cylinders, and sent it up to look around. Early the next day they walked the balloon forward a couple of miles. The wind got up, they hauled down and began to move back, then - as with Titania - a squall slammed the Duke to the ground and ripped it irreparably. The Duke had not been in very good condition when they first inflated her (him?) and it was becoming apparent that the harsh conditions (very dry, with hot days and cold nights) were not good for the goldbeaters' skin. It became, in the diarist's words, "very harsh and brittle in a very short time". The problem was largely solved when a supply of glycerine and neat's-foot oil arrived from base.(14) Nonetheless, the loss of two balloons so soon into the operations caused some consternation at RE headquarters, and the Section was instructed to deflate the balloons in rough weather, and not worry so much about the loss of gas (though it seems the Cape Town hydrogen plant wasn't fully operational until a week or so into January(15). On 26th December they inflated Eclipse, but when it grew squally the next day they discharged all her gas in the spirit of the HQ instruction. In addition to its directive the base also sent up two replacement balloons - but both turned out to be "very badly packed and in a hopeless state"! (16) Early in the new year (1900), on 6 January, Eclipse was inflated again, and attempted to spot the fall of shot from a naval 12-pounder firing at a laager(17) near Brown's Drift, behind the extreme left of the Boer positions, but the distance was too great to see clearly. The next day a sandstorm erupted and they had to empty Eclipse once more; despite this precaution it sustained damage. Raleigh (but not the Diary) mentions an undated occasion when a balloon was able to direct howitzer fire onto a gully where the Boers' ponies would otherwise have been hidden from view; the grisly head count was over two hundred equine corpses.(18)

There are two Diary entries (10& 12 January) referring to a '370' balloon. Ward also mentions these in his Manual, along with '120' balloons.(19) They were normally employed to take the weight of the cable off a tethered balloon so that it could rise higher. To do this two or three would be attached at intervals along the cable's length. In the present case however, the '370' was sent over to assist the wireless telegraphy section - almost certainly to lift an aerial, though this is not stated.(20) It was filled in the morning at the telegraphers' post. Before midday, it had broken away and been shredded in a sandstorm.

For the rest of January the Section used Triton, and carried out some routine but apparently not especially profitable ascents. High winds and sand-storms continued to interrupt their work, and Triton had to be deflated at least once to avoid damage. On 4 February it was caught out, and its career ended.

In mid-February, Cronjé was outflanked and obliged to vacate his position. Large reinforcements had arrived on the British side (plus a new C-in-C, Lord Roberts), assembling about 20 miles south of the Modder River lines. To them were added troops withdrawn from those lines, so that only a screening force remained to convince Cronjé that nothing was afoot. Having assembled sufficient wagon transport to make him independent of railway lines for several weeks, Roberts threw dust in Cronjé's eyes with feints towards and to the west of Magersfontein while he launched his steamroller eastwards towards Bloemfontein, capital of the Orange Free State, and Cronjé's supply base. When he estimated he had cleared Cronjé's left flank outposts, Roberts sent a 5000-strong cavalry force northwards across the Riet and Modder rivers with orders to then ride hell-for leather around the back of the Boer position to relieve Kimberley.(21)

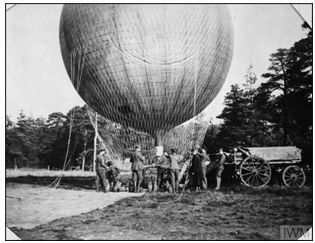

Fig. 2 A spherical balloon being prepared for launch.

The net and handling ropes are clearly

visible in this photograph

It was important that these moves should at least get under way before Cronjé became aware of what was happening. To this end, the Balloon Section was instructed on 12 February to keep an eye on Cronjé and immediately report any significant Boer troop movements. So Elsie was inflated and ascents made intermittently over the next few days whenever the wind permitted. On the 14th the balloon reported skirmishing well to the east as Roberts brushed against the Boer left flank (he hadn't quite cleared it); on the 15th they were able to report a dust cloud - French's cavalry - entering Kimberley, and on 16th, that the Magersfontein Boers had at last decamped (they were hurrying back westwards to defend Bloemfontein).(22) Later that day Elsie was badly ripped; she was packed up and sent back to Cape Town to be repaired.

Late on the 19th February, the Section moved off to join Robert's main force heading eastwards, with Lt Grubb in command, Capt Jones having reported sick some days earlier. They caught up early in the morning of the 20th on the south bank of the Modder at an obscure drift with the name of Paardeberg(23). Here they were to carry out some of their most valuable ascents, for this was also the place where the British had caught up with the retreating Cronjé. He was too encumbered with a slow-moving wagon train to slip away and was thus obliged to give battle, digging in on the banks of the Modder to create a fortified laager.

There were several reasons why the Paardeberg Drift location enabled the balloons to make a worthwhile contribution. First of all, it was a positional battle, not a running one, so the balloons' rather slow and plodding powers of movement were not an issue. Secondly, the landscape was open, with little in the way of defilades (except the actual river banks). Lastly, the General in charge (Kelly-Kenny), having learned that brave charges against entrenched Boers armed with Mauser rifles was a good way to invite a bloody defeat, decided to leave the job as far as possible to the artillery - and helping artillery was one of the balloonists. strong points. (Kitchener, recently arrived in South Africa as Lord Robert's Chief of Staff, and with experience of launching brave charges against natives armed for the most part with nothing more lethal than spears, had not yet learned the lesson, and ordered Kelly-Kenny to launch infantry attacks, which failed - bloodily.) Thereafter, the artillery was allowed to take over.

At 6a.m. on 24th, the Section began inflating the Duchess of Connaught; but the wind was too strong for ascents until the afternoon, when a first sketch(24) of the Boer position's layout was made. Early the next day, in good flying weather, a more accurate sketch was made. This enabled the gunners to select their targets, and inthe afternoon the balloon worked with a howitzer battery, directing its fire "with considerable success", claims the Diary. Ascents were not called for on the 25th, but on the 26th they began at dawn, making further sketches and taking some photographs, before correcting the fire of three field batteries by means of flag signals.

Lt Grubb, who carried out the Paardeberg ascents, felt that rather than flagging messages to gunners 2½ to 3 miles (4-5km) distant across the laager, the orders should have been shouted down to the ground and then passed on to the batteries by telephone (Diary, 26 Feb., note). The Official History endorses this by stating "... the exchange of messages between the [basket] and the batteries left much to be desired. The signallers with the balloon repeatedly failed to attract the attention of those with the guns..(25) The unstated implication of this debate is that if there was an integral telephone wire in the cable (see the account below of Section 2's experiences in Ladysmith) it was broken. Alternatively, their cable had no such wire in the first place; the absence of any Diary references to such a thing, or to telephone equipment in the basket, suggests this is the more likely conclusion.

The Boers - who as always hated the balloon(s) - fired tirelessly at the Duchess, and though the Diary reports little damage(26) she was not holding her gas well (perhaps as much from wear and tear as from Boer bullets).

With clearly no rescue in sight, and with his wagons and animals pulverised by the British artillery, on 27th Cronjé surrendered.(27) On 7 March the advance to Bloemfontein resumed in earnest, and in preparation for anticipated work ahead, the gas in the now bullet-holed and slackening Duchess was transferred to the (presumably?) smaller Bristol. Advancing through the day, with Boer scouts falling back before them, the balloon was aloft several times, and looked forward to rendering assistance during the attack on the Boers' next defensive position astride the river at Poplar Grove. The balloon ascended, ready to give assistance, but there was no attack: the Boer commandos had mostly lost heart after Paardeberg and melted away at the sight of cavalry working around their southern flank. They melted away at Bloemfontein, too, which was occupied without a fight on 13 March.

For the time being there was nothing for the Section to do in the way of ballooning. They had deflated Bristol on the 9th and packed it away (gas cylinders were again on hand for when the next inflation was required). For the rest of the month they carried out what in effect were odd jobs here and there - quite often wood cutting. At the beginning of April equipment was re-arranged and adjusted to allow the Section to fly two balloons simultaneously if needed. Supplies trickled in from Cape Town: more cylinders of gas and two additional balloons (both "in good condition, but very old.)"(28)

On 1 May 1900 the force began its advance north from Bloemfontein, with Pretoria as the ultimate objective. Minor skirmishes took place with small groups of Boers, and a more significant engagement on 05 May as the Boers briefly defended the crossing of the Vet River. However, Bristol was not called for until early the next morning, when it was filled ready to ascend to see if the drift was still held by the Boers. But before this ascent could be made, scouts reported the Boers had all cleared off. However, as the weather was calm, rather than deflate the balloon it was towed along within the column, bobbing about a few feet above its wagon ("like the pillar of cloud that led the hosts of Israel", was Winston Churchill's overwrought description.(29)) On the 9th, near Zand River, another reconnaissance of suspected Boer positions was called for, and the balloon was soon able to report Boers were retreating.

The advance continued through Kroonstad and Vredefort to Germiston on the outskirts of Johannesburg, the latter being reached on 29 May. Two days earlier Belfast, having been towed aloft for about 22 days, and with only a few cylinders-worth of topping up during that period, was deflated, still in good condition, and packed up. The day before deflation(25th), in the cold of the early morning, Bristol was slack and wallowing(30) and the Section resorted to tying a rope fairly tightly around the balloon about four feet(one metre) up from the base. This ingenious expedient temporarily reduced its volume and consequently rendered it taut again.

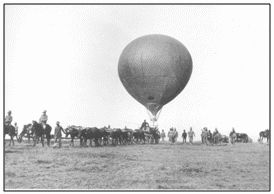

Fig. 3. A Balloon being drawn across the veld by

a span of oxen during the advance to Pretoria 1900

(Probably Section #01)

This was effectively the end of Section 1's active ballooning. They moved on to the Pretoria district and then (on 19 July) began moving east in the wake of Robert's advancing columns, in anticipation of contributing to whatever action might unfold. But the war was beginning to enter its guerrilla phase: the Boers planned to be masters of the veld, not landlords of bricks, tin and mortar. (A rather one-sided fight out to the east at Bergendal on 26 August, in which the balloons did not participate, was the last pitched battle of the war). With no role to play, and having reached as far as Witbank, they were turned round and marched back to Pretoria, with the men mostly reassigned to standard RE duties. On 29 November 1900, the Section officially ceased to exist.

(To be continued. Note: a full list of sources will be given at the end of Part III.

Notes

About the Author

Brian Culross wrote about military balloons in Paris in the June 2020 Military History Journal; an opinion piece about Napoleon as well as several poems in the June 2021 MH Journal and about the plight of widows in WWI a year later. Several more of his poems as well as a surprise from Patience Strong also came from his pen. This is the first part of three about balloons in the South African (Anglo-Boer) War.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org