The South African

The South African

As WW2 secrets go, that involving the Price-Milne Organisation managed to be buried among a very few documents that have surfaced some three-quarters of a century later. That its very existence should have been shrouded in such secrecy tells its own story. One of the numerous issues that confronted the Prime Minster, Jan Smuts, during the war was the division that existed among his own people, the Afrikaners. The fact, too, that a highly secret body, set up in 1940, was to be involved in the equally secret and complex problem of detecting clandestine radio communications offers one explanation as to why it has remained so obscure. But there are also others too, which this article will reveal.

The story of Felix (Lothar Sittig), the Nazi spy in South Africa and his radio transmissions to Germany, has been told in various places and with varying degrees of accuracy before. To those needing a refresher, or perhaps for those coming to it for the first time, refer to the author's articles that appeared in this Journal in 2019 (see the Notes below). As mentioned there, none of the information that reached Berlin from Sittig's Morse key contained much, if any, worthwhile military intelligence. And this was just as Dr Hans van Rensburg, the leader of the Ossewabrandwag (O.B.), had intended. Van Rensburg was absolutely insistent that nothing should be transmitted which might endanger the lives of South African troops either in transit by sea to the Middle East or of those already engaged in the battles raging thereabouts.

Fig.1 Lothar Sittig aka "Felix" in his

later more serene years.

Needless to say, this led to some consternation and bemusement among those Nazi agents in South Africa charged with collecting and then transmitting that information either to Lourenço Marques (now Maputo), for onward transfer to Germany, or directly thereto by Felix after his first successful transmission to Berlin in June 1943. Given van Rensburg's severe restriction on its contents, most of that illicit wireless traffic, however, turned out to be of little military assistance to the Nazis. Of some consolation to the O.B. was the broadcast the night after Felix's significant feat. Then, Radio Zeesen, the powerful shortwave transmitter in Germany transmitted, during its regular Afrikaans programme aimed at South Africa, the liedjie "Opsaal Boere". This was the agreed signal that Felix had indeed managed to reach Berlin from his transmitter in the veld near Vryburg. It delighted the O.B. who had, until then, to content themselves by listening to Zeesen's Afrikaans service with the comforting tones of 'Neef Holm', 'Neef Buurman', 'Neef Bokkies', and others issuing forth from loudspeakers hanging from trees out in the platteland.

Soon after the outbreak of war it had become apparent, both in Pretoria and in London, that efforts were under way in South Africa to subvert the country's involvement in the war as an ally of Britain. Opposition among many Afrikaners ran deep, with anti-British roots that went back at least as far as the Anglo- Boer [War] of forty years before. The Smuts government knew, from the outset, that they would be fighting a war of two fronts, with one being the active fifth column at home that required constant vigilance and careful handling.

Fig. 2 Felix's 250 W transmitter showing

one of its power amplifier valves stolen

from a diathermy machine at the

Bloemfontein hospital.

In February 1940 the Directorate of Military Intelligence was created in Pretoria. The brief given to Lt Col E.G. Malherbe, who soon assumed the role of Director, was wide-ranging - from intelligence and security to censorship and propaganda. But Malherbe's major function was to coordinate the Army Education Scheme whose purpose was to inform South African soldiers about the ideological issues of the war and the implications of Nazism for South Africa. The task of identifying and pursuing the Nazi-supporting malcontents within South Africa, and especially that of apprehending the Nazi agents at work there, fell to the police. Unfortunately, the police as well as the military, and much of the civil service, had within their ranks many who were active members of the O.B. with its overt sympathy for Nazi Germany. In addition, the Broederbond, the ultra-secret Afrikaner brotherhood with its steadfast belief that they had a God-given right to make South Africa their own, exclusively, while severing all ties with their despised enemy, the British nation, deeply fractured the unity among their fellow Afrikaners. Thus, internal security within South Africa was seriously bedevilled by these fractious factions.

Col. Lenton, formerly in the Post Office, had been appointed as Controller of Censorship and would now be responsible for coordinating all such intelligence work. The new Commissioner of Police, following the transfer of Col. I.P. de Villiers MC, to the army in the rank of Major General as commander of the 2nd South African Division, was Col. Baston. Unfortunately, Baston was no mental colossus and thus did not enjoy the confidence of those either above or below him. It was apparent, too, that he was heavily influenced by his deputy, the Chief of the C.I.D., Lt Col Coetzee, whom many suspected of being an active O.B. member and some even suggested he was a member of the Broederbond. Both claims would be hotly contested many years later but at the time Coetzee was treated with considerable circumspection. British Intelligence, in the form of MI5, MI6 and even the SOE would soon become directly involved in South Africa. The first officers to arrive in April 1942 were Lt. Col. Webster and Maj. Luke of MI5. Maj. Oliver of MI6 arrived shortly afterwards. Sometime later they were followed by the SOE's special envoy, Lt.-Col. Taylor. Across the border in Mozambique, Malcolm Muggeridge, the well-known journalist and author, was the MI6 agent who was based in Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) for the purpose of keeping an eye on the German consulate there which was suspected of running Nazi agents in South Africa. Webster, an expert on port security, concentrated on all maritime matters from his headquarters in Cape Town while Luke took responsibility for counter-espionage and counter-sabotage activities. At the beginning of 1943 Luke was succeeded by Maj. Ryde who then moved to Pretoria so that he could liaise much more closely with the South African Police who, in the absence of an adequate national intelligence structure, even within the military, had been instructed by the Smuts government to handle all matters to do with espionage and security. But, as it soon transpired, relations between the British security services and South Africa's police became rather delicate and were often the source of much friction between them. This soon turned to distrust and it was agreed that no intelligence in the Most Secret category would be passed to the police nor were they to receive any MI5 ciphers. Routine intelligence material would be sent directly to Lenton who was regarded as being utterly trustworthy while that in the Most Secret category would be given verbally to General Smuts alone by the British High Commissioner.

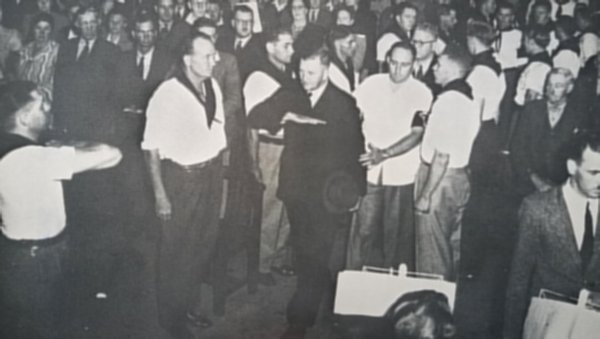

Fig.3 Hans van Rensburg acknowledges the salute

from his Ossewabrandwag Stormjaers.

Meanwhile, the Ossewabrandwag was becoming increasingly active. The harassment of soldiers home on leave had become a common occurrence while acts of sabotage and even murder were soon being attributed to them. As might be expected, the O.B. structured its so-called military wing, the Stormjaers, along lines not dissimilar to the Kommandos of the Anglo-Boer war. In order to coordinate their activities, some means of communication between them was necessary and so a cottage industry of building low-power radio transmitters took off. As early as 1941, in garages and garden sheds around Johannesburg and Pretoria, those O.B. members with suitable skills were hard at work. In one instance the residence in Sydenham, Johannesburg, of Kowie Marais, who would later become a judge before undergoing a political metamorphosis as an M.P. of the Progressive Party, was a hive of such industry. Soon it was reported that there were fifteen Morse code transmitters under construction. To prevent certain chaos required coordination and van Rensburg appointed his adjutant Heimer Anderson to take charge of all the O.B.'s wireless communications. It now became a high priority of Lenton's organisation to be aware of what information was passing between those Kommandos and so monitoring of its radio transmissions became a high priority.

As early as April 1940 the Royal Navy base in Simon's Town, as well as those at Durban and Port Elizabeth harbours, had listening stations, known as the Y Service (Y meaning wireless, of course!). In addition, there was another at Roberts Heights, the military base just outside Pretoria [now Thaba Tshwane, having become Voortrekkerhoogte post-1948]. They had all been established following considerable support from the South African Army's Director of Signals, Col. Collins. It was at Simon's Town that the RN personnel, under the command of Lt.Cdr. Bennett RNVR, were listening for the radio transmissions of German U-boats off South Africa's coast when they surfaced at night to recharge their batteries and to communicate with their headquarter ships. Soon those Y stations also undertook radio direction-finding (DF-ing) in order to try and locate the various transmitting U-boats. Stations were established at seven different localities from near Cape Town in the south, at those major ports where the Y Service was functioning, and even as far north as Bulawayo in the then Rhodesia. It would become apparent that bearings taken and plotted by some of those Y Service DF stations were sometimes very wide of the mark. For example, one of those illicit transmitters, presumed to be operated by Nazi agents, was indicated as being in Swaziland (Eswatini now) while another was apparently in Bechuanaland. (Botswana today). Both seemed most unlikely but, as will emerge, the Bechuanaland bearing may well have been pretty accurate since a site near the Molopo River, on the border up there, was favoured by Felix when the search to find him really hotted up. Experts were consulted and it was pointed out that direction- finding by radio was a complicated subject influenced by many factors, one of which was the propagation path followed by the radio signals in question. DF-ing over relatively short distances was far more accurate than if the DF station and its target transmitter were hundreds, or more, kilometres apart. In the case of radio signals propagated via the ionosphere, errors could be a caused by a number of phenomena, some of which were little understood at the time. The only solution was to have DF stations much closer to the suspected target areas. In addition, they had to be supported by mobile equipment capable of moving even closer to the targeted transmitter as needs be.

This realisation was the impetus for the establishment of the South African- designed and operated DF network which came into being, under oblique cover, as the Price-Milne Organisation. The proposal for its formation was made to Smuts by his Director-General of War Supplies, Dr H.J. van der Bijl who, afterwards, said he acted on a hunch since his knowledge of radio was very rusty. In fact, van der Bijl's modesty belied his considerable experience in the field. Many years before, when employed by Western Electric in the USA, he had been a pioneer in the development of the radio valve. His 1920 textbook on thermionic valves was the first to have been published on the subject. That technology formed the basis of all modern radio communications, television and radar, and much else besides. Smuts readily agreed to the construction of a DF network but insisted that it must be done in great secrecy and, most certainly, not under the auspices of any state security agency. How this would be achieved he left to van der Bijl. Knowing, as he did, the scope of engineering capabilities in South Africa, van der Bijl turned to the Electricity Supply Commission (now Eskom) and to the Post Office. Both had highly comptent engineers and large engineering facilities. He therefore called on E.T. Price and M.J. Milne, from those organisations, and appraised them of the country's very special need for an adequate DF system. As it turned out, Price had had a long interest in radio while Milne's Post Office engineers had already begun looking at the DF problem and they soon produced a prototype. However, neither the Post Office nor the Electricity Supply Commission had any spare capacity in their workshops, which were fully committed to other war work. They recommended to van der Bijl that he should approach the South African Railways with its extensive work-shops at Langlaagte, near Johannesburg. This was done and shortly thereafter they set about constructing the equipment while also making useful improvements along the way. The design of the hardware had been undertaken by engineers from South African universities plus a couple from the local radio industry. All had been very carefully selected by Price and Milne themselves and those men immediately went into uniform as officers in the South African Corps of Signals and hence under the command of Col. Collins.

Fig.4 The Price-Milne Organisation 1941-1944.

Standing left to right: Lieuts.Stirling, Jacobs, Price (jnr.) Wessels, Gordon.

Inset N.Troost.

Seated: Capt. Harvey, Messrs. Milne, Price (snr.), de Villiers, Capt. Roberts.

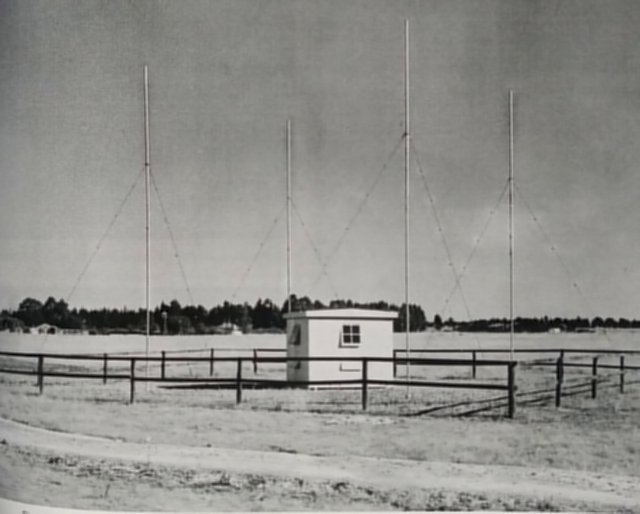

The fixed DF stations made use of the long-established technique of deploying four vertical antennas in what was known as an Adcock array. The antennas were each connected to an instrument known as a goniometer which was housed within the DF hut situated centrally between those antennas. The goniometer, as it was rotated by an operator, enabled the combined signals from the four antennas to be heard on a suitable radio receiver with just a single rotation being all that was required to produce the bearing of the transmitter being sought.

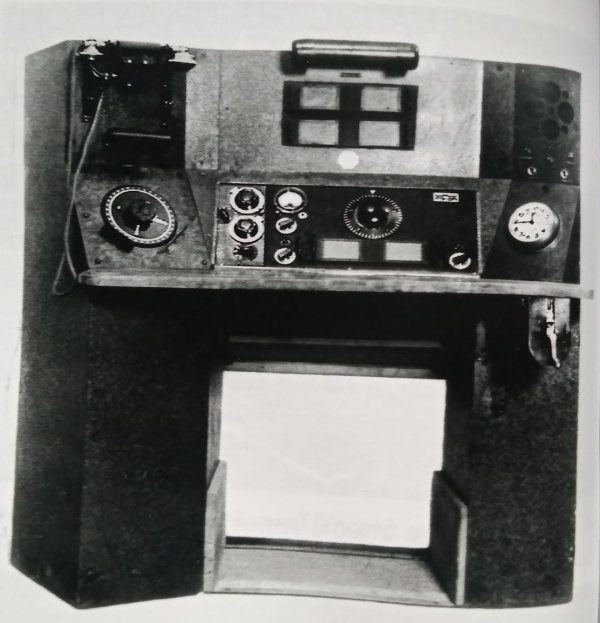

Fig.5 A complete DF console containing its

imported US-made HRO radio receiver with

the goniometer on the left.

Obviously, the accuracy of the process depended on many factors associated with the construction, erection and calibration of the equipment, as well as on the skill of the DF operator. Having obtained a bearing he then communicated it by telephone to a control station that was in communication, by the same means, with many other DF operators sitting within their DF huts. Speed, of course, was extremely important because it was necessary to obtain a bearing before the suspect transmitter ceased operating.

Fig. 6 The Adcock DF array showing

the four vertical antennas with the

receiver/goniometer hut in the middle.

The mobile DF station was very different. It consisted of a suitably capacious civilian motor car which had on its roof a rotatable antenna. Inside, the operator with his DF receiver would rotate the antenna to locate the transmitter, having tuned the receiver to the frequency of the illicit transmitter. He would then immediately send that bearing information, by radio, to his control station.

Fig. 7 The civilian motor car of the mobile DF unit

with its rotatable loop antenna on the roof.

Quite how many DF stations were manufactured remains unknown: van der Bijl mentioned 'large numbers' while another source claimed it was as many as a hundred. That latter figure seems unlikely but we can be sure that a significant number went into service. All the operators, who received intensive training, were also very carefully vetted and were sworn to secrecy. It was only many years after the war that some even breathed of what they had been doing.

Once the DF system became operational the decision was taken to transfer it, and all its operators, lock, stock and barrel, to the Royal Navy in Simon's Town where Lt. Cdr. Bennett had been controlling his own DF network of stations for some while. Henceforth, all bearing information would be sent to Bennett's headquarters for an initial assessment followed by onward transmission by telegraph to Col. Lenton in Pretoria where the decision would be taken on whatever follow-up procedure was deemed to be necessary. And this is where the problems came in. Any follow- up action that might lead to the arrest of suspects presumed to be operating an illegal transmitter was a matter for the police and that meant Col. Baston and his deputy Lt. Col. Coetzee, the man much mistrusted by British Intelligence.

All O.B. radio transmissions, and especially, from June 1943 onwards, those directed to Berlin by Lothar Sittig using his powerful transmitter - located near Vryburg in a hole in the ground close to Hans van Rensburg's farm - were not only being monitored by the Y Service but every effort was being made to find where they were by means of the joint RN and South African DF networks. In addition, all those encoded messages, received by the Y Service, were then sent immediately, via the RN's dedicated telegraphic link, to the British Government Code and Cipher School (G.C. & C.S.) at Bletchley Park for their attention. Since none involved the use of the Enigma machine those O.B. codes, which were fairly straight-forward additive letter-substitution ciphers commonly used by commercial organisations, and were easily 'broken' at Bletchley.

When the police went into action, and arrived at a designated location, it turned out repeatedly that the suspect had long- since disappeared along with his radio equipment. In the case of Felix, who was the focus of considerable DF activity, word of an impending police raid always reached Vryburg well before a single policeman did and it was assumed that the network of O.B. supporters, or their informants, within the police force were stymying every such operation. Lothar Sittig and his Nazi colleague Nils Paasche (or Pasche in some sources), with the enthusiastic assistance of the local O.B. supporting farmers, rapidly covered up the hole in the ground, within which was the transmitter and its petrol generator, and then dropped the two 20m high poles that supported the wire antenna directed at Germany. Both the entombed transmitter and those hastily buried poles were then covered with the local undergrowth and the area soon resumed its original veld- like appearance. On some occasions, when even more advance warning was given, Sittig and Paasche, plus the transmitter, antenna and the petrol-driven generator, decamped to the Molopo River some 50 km away and simply re-established their clandestine radio operation from there. Such was the confidence that van Rensburg had in his O.B. desperados and their ability to defeat the dreaded British enemy and their 'traitorous' fellow Afrikaners.

Smuts, needless to say, was fully aware of all this. His personal standing within the highest echelons of the British government, particularly at the very highest level - Winston Churchill - made him and his position absolutely impregnable. But that did not mean that those lower down the British intelligence chain, such as the MI5 and MI6 representatives in South Africa, could understand Smuts's reluctance to act against van Rensburg when so much evidence seemed to exist which indicated his duplicity, or worse, as an openly-professed Nazi sympathiser. But then few foreigners understood the complexity of South Africa's almost unique divide between its two communities of European heritage. Smuts's own son probably expressed it best when he wrote 'My father tolerated all these [dissident Afrikaner movements], as well as the far more dangerous Broederbond with the aggravating patience born of long experience'. Aggravating patience indeed as far as his British allies were concerned.

As the war entered its final year and the Nazi's (and Hitler's) demise was simply a matter of time, British Intelligence began to scale back their involvement in South Africa. Maj. Ryde, now acting on behalf of both MI5 and MI6, was the only British agent left there. His efforts to trace Sittig and the remnants of the Nazi's clandestine radio network, now rapidly disintegrating, were continually thwarted by Col. Coetzee. In addition, friction had developed between Ryde and Bennett at Simon's Town as to the best way of apprehending Felix. None of this was helped by the return of General de Villiers, the former Commissioner of Police, from 'up north' and his appointment as the commander of all forces defending South Africa's coastal area.

Once briefed on the enemy agents and their wireless communications exploits, he sought to take charge of the operation to round them up. The fact that de Villiers refused to be deflected from his belief in the absolute loyalty of his former CID chief, Coetzee, immediately brought him into conflict with the newly promoted Brigadier Lenton in Pretoria who was still manfully running South Africa's intelligence activities. Lt.Cdr. Bennett went behind Ryde's back and approached de Villiers directly. Together they agreed that a raid should be mounted against Felix's hideout in Vryburg. But Bennett was unfamiliar with the use and operation of the mobile DF units and the raid was a disaster, yet again. General Smuts was furious with de Villiers while Ryde blamed Bennett.

Then Col. Coetzee died suddenly in July 1944. By then, the Director-General of MI5, Sir David Petrie, had already taken the decision to close the joint MI5/MI6operation in South Africa and Ryde returned to England. Petrie's remarks summedup the pretty dismal situation: '[It] offends all one's professional instincts to leave thiscase in this untidy state [but the] obstacle is the unreliability and incompetence of the police and the unwillingness of Smuts to drag van Rensburg and his fellow conspirators into the open.'

Given all this, Lothar Sittig was able to sit out the war having received, early in 1945, a final message from Berlin portending the end. He was never apprehended.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement is made to the South African Institute of Electrical Engineers for permission to use photographs from D. J. Vermeulen's two-volume work 'A History of Electrical Engineering in South Africa: 1860-1960'.

I thank Evert Kleynhans for the many documents he let me have from the Ossewabrandwag archive, originally in Potchefstroom and now in Pretoria.

In addition, I thank the curator of the museum at the Voortrekker Monument, near Pretoria, which now houses those documents, for permission to photograph the transmitter used by Felix.

I also acknowledge the many technical discussions I had with my engineering colleague, Vincent Harrison, who studied the transmitter in detail and with whom I collaborated in writing the article about it.

Notes

About the Author

Brian Austin studied electrical engineering at Wits and then spent a decade developing radio equipment for use underground in the mines. After becoming a senior lecturer at his alma mater he emigrated to the UK in 1987 having served as a reserve officer in the South African Corps of Signals for many years.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org