The South African

The South African

Abstract

One of the most charismatic characters of the German South-West African Campaign was Captain de Meillon. His legacy mixes the daring and dash of a (possible) spy with the bravery and ambition of a soldier's soldier. de Meillon can be compared to a modern day special forces soldier as an energetic intelligence officer commanding the scouts for the Imperial Light Horse Regiment. This article sets a broad context for de Meillon's exploits against the development of the campaign of the Southern Force under Beves and later McKenzie between Lüderitzbucht and Aus. The main contribution of the article is however in combining previous unpublished material contained in the diary of Captain Ivor Guest (Witwatersrand Rifles) so as to attempt a reconstruction of the ambush and ambush site that ultimately cost de Meillon his life. de Meillon's charisma resulted in the exploitation of his demise for propaganda purposes in the press and also by the Union Defence Force High Command.

de Meillon as a propaganda asset

Much of the source material dealing

with Captain de Meillon's exploits and

death originates from a fundraising book

published in 1916, written by a pair of

Reuters journalists embedded with the

Union Defence Force. The book: How Botha

and Smuts Conquered German South West

(1) provides source material for

most information published since then on

de Meillon.

(2). The contemporary context in which

this book was written is clearly

reflected in its content. The 1914 Rebellion

was still a fresh memory and reconciliation

between the Anglo-Boer War combatants

not yet assured, the integration of

Afrikaans-speaking and English-speaking

soldiers in the Union Defence Force

(UDF) not yet complete and a lack of

unified political support for the participation

in the war in the general population.

(3) There was an obvious need for

a narrative to support reconciliation in the

broader (white) population and integration

within the ranks of the UDF. de Meillon's

background and natural soldier's soldier

charisma was a perfect fit to act as a role

model for such a propaganda narrative:

de Meillon as a military intelligence asset

de Meillon likely spent the better part of a decade around Lüderitz between his release as POW and his return to South Africa. As a result he would have had a very good understanding of the infrastructure and military assets of the area. His knowledge of the Lüderitz area was obviously advantageous to the Union Defence Force. In fact, his pre-war presence and his profession as a photographer seem to have convinced the Germans that he was a spy.(5)

Whereas the Union of South Africa did not have had strong strategic intelligence, the same cannot be said of Britain. The most well-known intelligence source on pre-WWI GSWA available to Britain was Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Trench, DSO. A decorated Boer War veteran, Trench served as British military attaché to the German headquarters in GSWA from 1905 to 1906 during the Herero and Nama uprisings and in Berlin thereafter. A fluent German speaker, Trench impressed Kaiser Wilhelm sufficiently with his Hoffähigkeit to request Trench by name to serve as amilitary observer in GSWA. Trench's secret field reports were sent to his military superiors and to the governor of the Cape Colony who forwarded them to the Foreign Office in London and the British Embassy in Berlin. For a little over a year, Trench submitted his observations on Von Trotha, the insurgency, the Schutztruppe and German intentions towards the Cape Colony. A great deal of his reporting can be found in the British Army intelligence handbook: "Military report on German South-West Africa", that was first printed in 1906 and re-issued in 1913. From archival records, it is clear that much of the handbook was taken verbatim from Trench's reports and those of his successor, Major Wade. Trench also submitted a number of maps that would have been valuable to a military planner, including details of the German communications network in the protectorate, showing rail, telegraph, and heliograph connections throughout the country.(6)

Figure 1: A pre-WWI photograph of the

Lüderitzbucht pier attributed to de Meillon.

The military intelligence value of

such a picture is self-evident.

The important strategic military infrastructure assets Trench pinpointed included the radio masts, the submarine telegraph cable, the wharves and piers at Swakopmund, and the water desalinisation condensers at Lüderitzbucht. With the exception of the condensers, all of these sites were disabled or attacked in August and September 1914.(7)

General Botha especially attached much value to intelligence gathering(8), yet in contrast to the British military intelligence, the Union Defence Force at the time of its formation did not have the capability to conduct strategic long-term intelligence operations.(9) The main intelligence focus remained tactical, and consisted of scouting sections that were attached to mounted regiments and were seamlessly integrated into Commando units. Central to the Commando doctrine of mounted warfare was the continuous deployment of a scouting screen. Some 31 separate tactical scouting units consisting of 1 335 men made up the bulk of the intelligence capability against 68 men forming part of the Special Intelligence Unit.(10) New forms of intelligence gathering, radio intercept and aerial reconnaisance were also being used effectively.

It is therefore perhaps improbable, but not completely unlikely, that de Meillon provided information to the fledging Union of South Africa during the time he spend at Lüderitz. Given his profession as photographer, it is understandable that the Germans considered him a spy. This label would certainly have had a role in De Mellion's eventual fate.

de Mellion's exploits as a UDF soldier

When war broke out de Meillon, like many other Boer war veterans, rejoined and was commissioned with the rank of Captain with Colonel Beves's Southern C-Force. Attached to the 5th Mounted Rifles (Imperial Light Horse - ILH) as the commanding Intelligence Officer, de Meillon was in the thick of things during theSouthern Campaign.

De Mellion played a central role in the initial occupation of Lüderitz. The UDF expected the German forces to defend Lüderitz and destroy the condensation plant, lighthouse and wireless station upon withdrawal to Kolmanskuppe. Beves therefore planned a simultaneous flanking attack on both Lüderitz and Kolmanskuppe. To give effect to this plan it was intended to land an initial force of 300 men at North Long Island Bay, 13 miles south of Lüderitz, to cut the railway line at kilo's 21 and 5. This initial force would be supported by a similar sized reserve. The remainder of Beves's forces would then make a frontal sea-borne attack on Lüderitz itself. The weather however did not play along. The alternative plan then executed was to land a smaller party in batches under the command of de Meillon to destroy the railway closer to town, followed by a sea-borne frontal attack.

de Meillon and the first batch of men were successfully landed from the Galway Castle by a small whaler called the Magnet. The first boat landing was executed safely, but the whaler capsized upon return, leaving de Meillon stranded without tools or explosives. At this point a German patrol discovered the landing party and shots were exchanged. With the element of surprise lost, de Meillon's group started to walk towards Lüderitzbucht, arriving in the early hours of Sunday morning of 20 September 1914, in time to witness the final stages of a German withdrawal. Upon entering the town a well-lit abandoned house was found with a pot of warm coffee on the dining room table and beds still warm. At this stage, legend has it, de Meillon took a nap on one of the beds. With no news from the landing party, the Beves force approached Lüderitz the next morning with the view to land in force. When a landing party approached the shore to demand surrender, they witnessed a white flag being hoisted above the Town Hall. Lüderitz was surrendered and de Meillon's reputation established.

de Meillon was again in the thick of the action a week after the landing when a force of the 100 Imperial Light Horse supported by 250 Rand Light Infantry attacked a German contingent at Grazplats (11). The engagement opened at 1000 yards and concluded at 50 yards. The UDF suffered four dead and three wounded, one of which was de Meillon suffering a shot through the thigh.(12)

Figure 2: Google Earth map

Showing from Luderitz to Aus

Distance as the crow flies 180km.

North is to left

A Scouting mission gone wrong

Intelligence at Defence Headquarters fully expected the Germans to defend Aus. The escarpment rise towards Aus afforded strong natural defensive positions and the Germans were observed continuing to fortify positions at Aus Nek. The Germans indeed fortified a 5-mile long front from Aus Nek to Kanus Poort. It is important to remember that the UDF assumed German artillery superiority which would strongly favour the defence of prepared positions.(13) McKenzie was therefore reluctant to attack Aus without sufficient concentration of forces. The early stages of the Southern Campaign in GSWA were consequently mainly a campaign centred around logistics.

McKenzie's plan was a line of advance along the railway line from Lüderitzbucht to Kolmanskuppe, Grazplatz, Rotkuppe, Haalenberg, Tsaukaib and Garup towards Aus. Desert conditions meant that all supplies, particularly water and fodder, had to be painstakingly brought up by rail. The Germans demolished the line as they withdrew, forcing the reconstruction of the line with the UDF's advance. By 19 February 1915 the line reached Keishohe and the next objective, Garup. Garup was a strategic asset as it was expected to have good ground water supplies, an aspect that greatly hindered the UDF's advanceup to that point.(14)

de Meillon scouted ahead of the advancing UDF Infantry and found Garup abandoned by the Germans on the 21st of February 1915. Leaving Garup to the advancing UDF vanguard, de Meillon scouted on towards Aus during the night. Just before dawn on the morning of the 22nd, the de Meillon's scouting party was close enough to hear blasting and witnessed a train approaching from the direction of Aus. The Germans were in the process of breaking up and removing the Garup-Aus railway line when de Meillon's group engaged the work party from a distance of 1 500 yards. The Germans immediately stopped work and withdrew under fire with the train towards Aus. Almost immediately, de Meillon and his men observed dust at the foot of a kopje 3 miles to the north-west(15) at a known German position. de Meillon interpreted the dust as an indication that the position was being abandoned. At this point de Meillon remarked to Sergeant- Major Dreyer: "I knew these Germans will not fight. I'm almost sure we can go straight to Aus." de Meillon then proceeded to lead a canter towards the kopje. de Meillon and three Nama scouts were, with Dreyer and Sgt Meintjes(16) on the flanks of what seems to have been an open line- abreast skirmish formation. What happened thereafter remains somewhat mired in controversy.

The published version of events of de Meillon's ill-fated scouting party appears in Rayner and O.Shaughnessy's publication (17). This account draws upon the recollections of Sergeant-Major Dreyer. Dreyer was presumed missing in action and dead until it was later established that he was a prisoner of war. It was only after Dreyers's escape four months later that his account was captured by the journalist. Dreyers's account: "within 200 yds of the kopie a volley rang out and he lost his horse. de Meillon dismounted and returned fire, and it may be assumed that it was not without effect. Then a second volley spat out and the Captain fell in his tracks, shot through head and chest; two of the Hottentots(18) were also killed and the other severely wounded."

The other account, unpublished, is

contained in the diary of Captain Ivor

Guest(19) and related the story of

Sergeant Meintjes's first-hand account.

Guest mentions the de Meillon incident in

his diary entry of the 24th of February

1915:

"On the 22nd Capt. de Meillon,

Sergeant Meintjes and a number of

natives went on a patrol from Garup. Germans

opened fire on them from 50 yards

and all but Meintjes were killed."(20)

Figure 4: Enlarged copy of

pages from Captain Guest's Diary.

On the 3rd of March Guest's diary

reads:

"Meintjies, who used to belong to

this company, was out with Captain de

Meillon when he was killed and gives the

following description of the incident: 'The

patrol was advancing on the kopje. De M.

and the main party made for sloot A at X.

Meintjies was on the left flank a little in advance of the patrol. When de M party was 50 yards from X they came under a heavy fire from the sloot and the kopje. De M actually crossed the sloot A. Meintjies got back round the left flank & he says he was pursued by Germans to within 4 miles of camp.'"

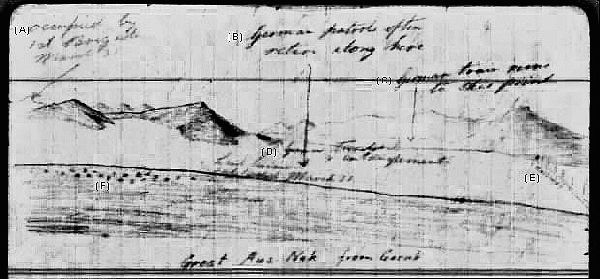

Figure 3: Potential movements of an ambush attack superimposed on the sketched area.

Reconstructing the drawing made by Guest would suggest that the de Meillon scouting party was engaged from both Sloot "B" as well as the kopje. If that is the case, de Meillon entered an ambush kill zone.

Rayner and O.Shaughnessy noted that de Meillon was buried where he fell, and that the Transvaal Scottish later remodelled the grave(21). The location is given as next to the road between Garup and Aus.(22)

A likely location of the ambush site described by the Meintjies account can be found using Google Earth Latitude 26°38.56.17.S and Long. 16°14.52.83.E is a possible location of the kopje. This kopje represents a dominant defensive position on the Garup-Aus road. Using this location, the drawing provided by Guest can possibly be reconstructed. Rayner and O.Shaughnessy mention that de Meillon approached the kopje towards his northwest. A tactical German ambush using the dry riverbed makes sense, especially if de Meillon's approach was observed from the known German observation post on the kopje. It is likely that the Germans would have been alerted by the shooting on the rail demolishing party and would have had sufficient time to prepare the ambush.(23)

The position of the "x" is approximately 100m from the kopje and well within the 30-50 yards range for the ambush mentioned by Dreyer and Meintjies respectively. Given the distances of musketry at the time, the entire "kill zone" of the ambush site would have been within 100m, almost point blank range. This point blank range is also the root cause of the controversy associated with this incident as it is suggested that de Meillon was recognised and that he was specifically targeted by the Germans as a suspected spy.

If de Meillon's scouting party was in extended skirmish format, line abreast, and if de Meillon was located at the centre with the three Nama scouts, then Meintjies and Dreyer's respective positions on the flank would have been spread over a distance of at least 300m (assuming a distance of 50m between each horse). If de Meillon and the Namas were indeed in the kill zone, the concentration of fire on the centre can be explained and also the lucky escapes of Dreyer and Meintjies as they were possibly outside the ambush kill zone.

The controversy

de Meillon was described as "dark moustached, debonair"(24) and clearly a charismatic individual who was widely respected by the UDF troops. He was held in such high regard that there reportedly had been calls for him to form a scouting corps out of volunteers(25). However, he was also described as impatient and somewhat rash. The slow build-up by McKenzie prior to the attack at Gibeon apparently frustrated him immensely.(26) He was not alone in his frustration as Royston shared de Meillon's impatience at the slow pace of the campaign up to that point(27).

Utterances by de Meillon regarding his low opinion of the Germans and that they "would not fight" also speaks to a degree of arrogance in his personality. de Meillon captured Lüderitzbucht and Garup without a fight and may have expected to also enter Aus in a similar manner. However, at that stage of the campaign there was ample evidence of German troop movements observed on a daily basis in the Aus Nek area(28). It is therefore likely that de Meillon simply misread the tactical situation by confusing the dust observed at the foot of the kopje as a withdrawal. His arrogance however may have contributed to him applying insufficient caution, given the tactical situation. In some ways de Meillon's arrogance and opportunistic ambition to occupy Aus parallel the experience of General Custer at Little Bighorn.

It is rather obvious that Rayner and O.Shaughnessy were exploiting the de Meillon incident for its propaganda value by suggesting that the point blank range was tantamount to murder. The motive: the Germans recognised de Meillon and were convinced he was a spy. To add spice to the story, the three hanged Nama found in Aus were linked to the de Meillon incident as these men were suspected to have been hanged as spies as well. Yet, the report by Dreyer was clear that two of the three Nama with de Meillon were killed and the third heavily wounded. It would have been unlikely that anybody would go to the trouble of hanging dead men.

However, Rayner and O.Shaughnessy were not the only exploiters of de Meillon's popularity. The original propaganda value was clearly recognised by the HQ as is evident in the elaborate military burial conducted after the event. A large firing party of a hundred men, the attendance by his widow brought in from Cape Town and the voluntary attendance of hundreds of officers and men of "C" force suggest that the command was shrewdly allowing and enabling the exploitation of the incident for its propaganda value.

Figure 5: A possible location for the de Meillon ambush? (X)

Figure 6: Sketch from Capt Guest's Diary

Handwritten comments in the diary:

A Occupied by 1st Brigade March 31

B German Patrols often return down here

C German train runs to this point

D German trenches and entanglements

E Railway

F Land mines extended March 31 shown as crosses

Original pencil sketch in Diary

Figure 7: de Meillon’s grave at the

Aus Military Cemetery (30)

Reflection

On the probability of evidence, after more than a century, it is possible to conclude that de Meillon may simply have been a victim of his own ego.

However, it is also very likely that de Meillon's popularity would have elevated him to hero status if he indeed could also claim to have taken Aus without a shot being fired. As is often the case, the margin between death and being a hero is thin. In de Meillon's case destiny had a different outcome in store.

References

Collyer, J. (1939). Die Veldtog in Duits Suidwes-Afrika. Pretoria: Staatsdrukker.

Devitt, N. (1937). Galloping Jack: Being the Reminiscences of Brigadier-General John Robinson Roystone C.M.G D.S.O. V.D Order of Stanislaus of Natal, South Africa. London: HF &G Witherby Ltd.

L’Ange, G. (1991). Urgent Imperial Service: South African Forces in German South West Africa 1914-1915. Rivonia: Ashanti Publishing.

Paice, E. (2007). Tip and Run: The untold tragedy of the Great War in Africa. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Rayner, W. A. (1916). How Botha and Smuts conquered German South West. Cape Town: African World Cross.

Robinson, J. K. (1916). With Botha’s Army. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Stejskal, J. (2016). Go Spy Out the Land: Intelligence Preparations for World War I in South West Africa. Scientia Militaria vol 44, no 1, 35-46.

Trew, H. (1936). Botha Treks. London and Glasgow: Blackie & Son Limited.

Van der Byl, P. (1971). From Playgrounds to Battlefields. Cape Town: Howard Timmens.

Notes

About the Author

André moved to Namibia in 2024 and has a special interest in the colonial and precolonial history of the country. He is currently doing research on the small arms utilised in the pre-colonial conflicts, the later German period and WW1.

André is the Country Manager for a Civil Engineering consultancy firm which is involved in railway, water and housing initiatives.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org